In a previous article title U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Supply we discussed the increasing importance of fruits and vegetables imports to U.S. demand. Several factors could explain this increase in dependance such as high labor costs and availability relative to other countries, mainly Latin American countries, high cost for technology to help increase labor efficiency (if equipment is even available for the specific crop), longer seasonality and climate more suited for specialty crops, trade agreements, increasing regulatory costs, and subsidies to infrastructure or production in other countries. Labor cost and availability is identified by the literature as the main challenge that the U.S. fruits and vegetable industry faces; therefore, the next couple of articles will focus on this issue.

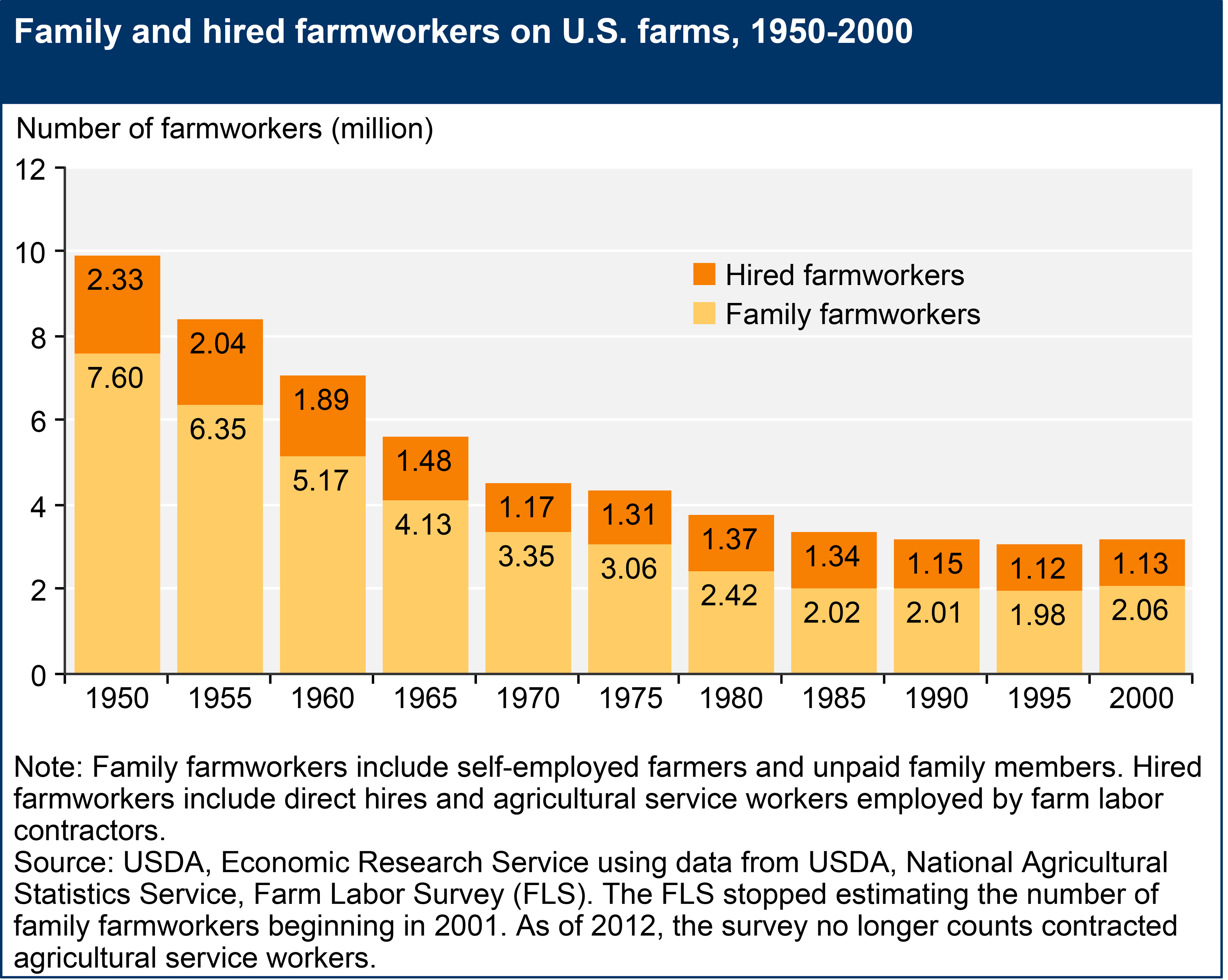

The average number of hired farmworkers has steadily declined over the last 50 years, from roughly 2.33 million to just over 1 million (Figure 1). Hired farmworkers make up less than 1 percent of all U.S. wage and salary workers, but they play an essential role in U.S. agriculture. Labor expenses are a major concern for agricultural producers in general, but even more for fruits and vegetable producers. Labor expenses for agricultural production accounts for around 10 percent of total operating expenses, however, labor expenses for fruits and vegetables are 38.5 percent and 28.8 percent, respectively.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) estimates from data spanning fiscal years 2018–20, just 30 percent of crop farm workers in manual labor occupations were U.S. born, therefore around 70 percent were foreign-born. Imported labor, primarily from Mexico, seems to be the major source of farm labor for fruits and vegetable production in the U.S. However, the decline of farm workers from Mexico has caused U.S. farm labor shortages. The main reasons for the decline are the sharp decline in the Mexican fertility rate, a significant expansion in rural education, and an increase in per-capita income, which is now close to $20,000 per year (adjusted for the cost of living). The good news for U.S. farmers is that there is a great deal of persistence in farm work. If a rural Mexican does farm work for one year, there is more than a 90 percent likelihood that he or she will do farm work the following year. The bad news is that a transition away from farm work is underway. The supply of agricultural workers will not disappear immediately, but U.S. agriculture can expect to see a gradual decline in the availability of Mexican farm workers over time.

This decline in migration along with increasing the state minimum wage, and removal of overtime pay exemptions by some states appear to have increased U.S. farm labor costs. The federal minimum hourly wage is $7.25 and has not increased since 2009, but some states set their minimum wage higher than the federal one. Also, the Raise the Wage Act of 2023, introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate on July 25, 2023, if approved would gradually raise the federal minimum wage to $ 17 an hour by 2028. Nevertheless, farm wages in the U.S. often exceed state minimum wages and are considerably higher than the Mexican minimum wage of $14 per day.

Figure 1. Family and Hired Farmworkers on U.S. Farms, 1950-2000

References

Economic Research Service (ERS). “Farm Labor.” Accessed February 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/. Updated August 7, 2023.

Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS). Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS). Online database. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx. Online public database accessed February 2024.

Ribera, Luis, and Landyn Young. “Challenges for U.S. Fruits and Vegetables.” Southern Ag Today 4(28.4). July 11, 2024. Permalink