Recent years have seen several high-profile outbreaks of transboundary animal disease. On average, approximately 0.01% of the world’s cattle population, 0.05% of the world’s swine population, and 0.03% of the world’s poultry population die each year due to global animal disease outbreaks.

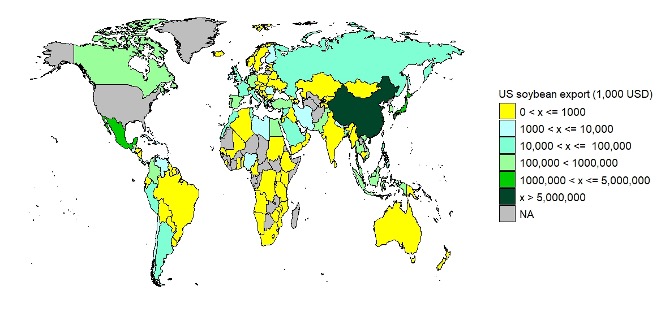

These disruptions cause losses not only in the animal production industry but also in other related industries, such as the feed grain markets. One such upstream industry which is important for Southern U.S. agriculture is the international soybean market. Soybeans are the predominant source of protein in animal feed, and over 95% of global soybean meal production is destined for animal feeding (about 76% of total crush by weight) (Economic Research Service, 2024). Between 2005 to 2020, the U.S. was the second largest exporter of soybeans in the world behind Brazil. U.S. exports account for more than 30% of global soybean trade. The top five destination markets for U.S. soybeans have historically been China, Mexico, Japan, Indonesia, and Germany (Figure 1).

Figure 1: U.S. Soybean Exports, by Destination Market

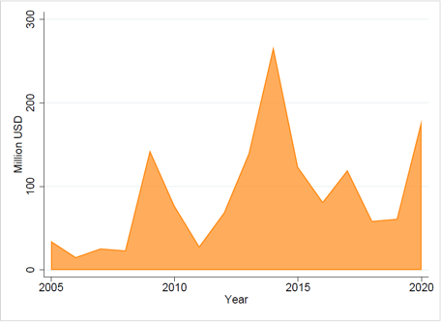

In a recent study, we use a statistical model to examine the losses to global soybean trade due to animal disease (Lwin, Schaefer and Hagerman, 2024). A significant amount of animal deaths within a short period represents a demand-side shock in the feed market, where soymeal is a primary protein source. Our analysis suggests that—on average—more than $96 million in export potential is lost annually due to animal disease outbreaks (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Annual losses in U.S. soybean export potential due to animal diseases

These results should be of interest to policymakers. Historically, animal health policies have focused primarily on compensation to producers of affected livestock, which may include indemnity for animals that die or are depopulated for disease control. Few policies address the risk animal diseases pose to upstream suppliers. Crop insurance programs, if available, may protect grain producers against price declines. However, crop insurance is unlikely to address additional costs of storage or quality loss for grain that must be stored for longer periods of time. Policy efforts to enhance supply chain resilience should consider the ripple effects of animal disease-related disruptions on related industries.

References

Economic Research Service, USDA. 2024. “International Baseline Projections.” Accessed: 2024-02-02.

Lwin, Wuit Yi, K. Aleks Schaefer, and Amy D. Hagerman. 2024. “Animal Disease Outbreaks and Upstream Soybean Trade.” Food Policy, 127: 102685.