With the trend of increasing urbanization, Urban Agriculture (UA) has emerged as a key strategy to address challenges like food insecurity and social inequality in urban development. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of UA by exposing weaknesses in the food supply chain and emphasizing the need for local food security (Clark et al., 2021). Community gardens, a common and impactful form of UA, provide spaces for residents to grow fresh produce in the community while offering environmental and economic benefits (Guitart et al., 2012; Kirby et al., 2021). In 2009, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) initiated the “People’s Garden” program to connect gardens across the U.S. that produce local food to address food insecurity and bring people together in their communities. Community gardens have become central to UA policies to enhance food security and environmental sustainability, particularly in low-income urban neighborhoods.

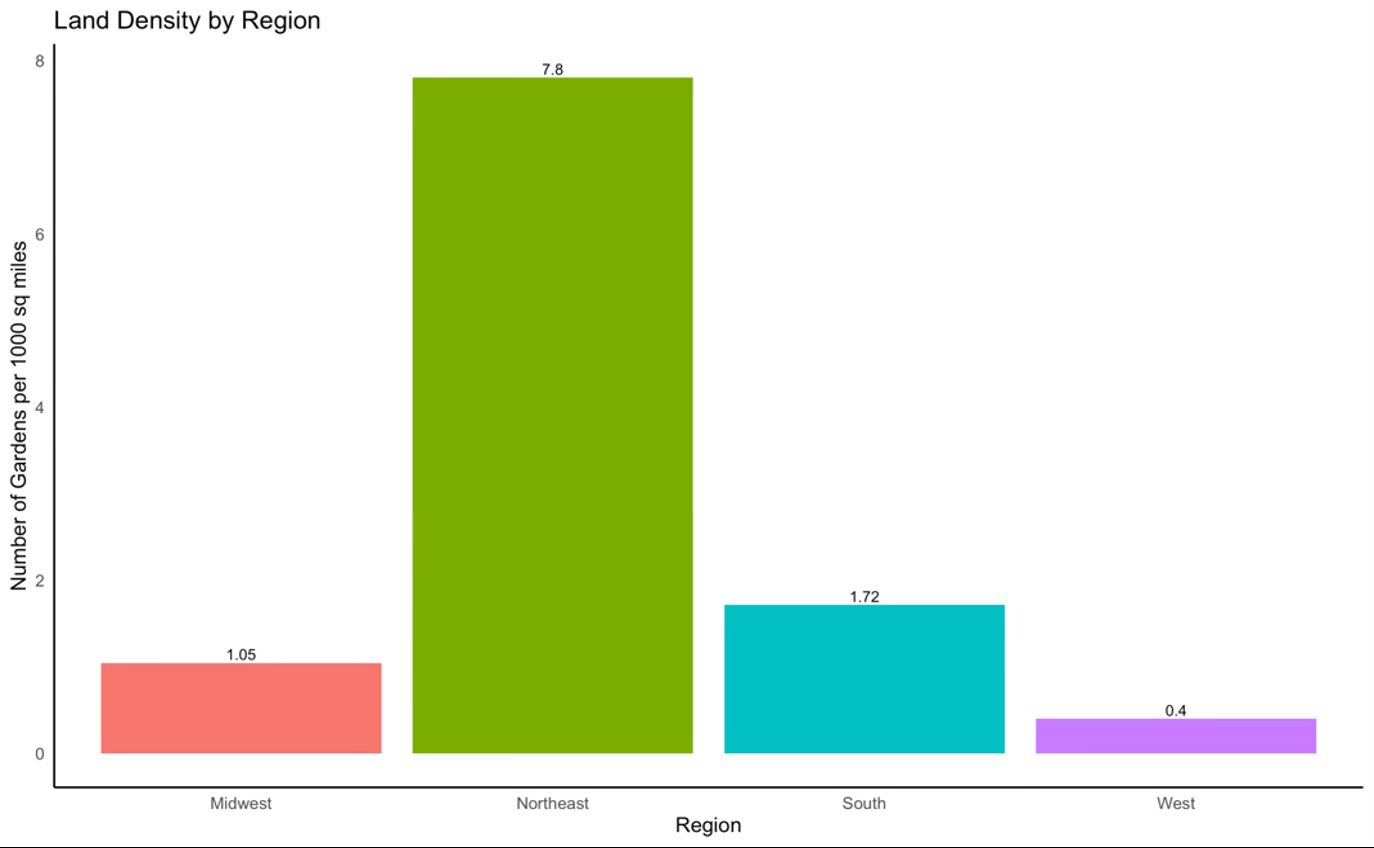

The need for such initiatives can be critical in the southern U.S., where food insecurity levels are significantly higher than in other regions. For example, although the South has less than half (45%) of the country’s total counties, it disproportionately represents areas with high food insecurity. Specifically, 84% of counties that experience high rates of food insecurity are located in the South (Feeding America, 2024). Community gardens and other UA efforts could play an essential role in alleviating food insecurity in these areas. The density of existing community gardens varies widely by region (Figure 1). Based on self-reported data from the American Community Garden Association, the Northeast has 7.8 community gardens per 1,000 square miles (green bar), while the South has fewer than 2 per 1,000 square miles (turquoise bar).

Figure 1: Distribution of Community Gardens by Region

However, there is growing interest in developing urban gardens in the South, particularly in Texas. For instance, Dallas was recently selected by the USDA as one of 17 cities for urban agriculture investment. The Houston Health Department recently launched the “Get Moving Houston Urban Gardens” initiative to promote healthy eating. Houston currently has over 160 community gardens, mostly in lower-income communities. While community gardens offer many benefits and can help address food insecurity and social inequality—especially in low-income, minority communities in the South—careful planning is essential to ensure these communities fully benefit.

There are important challenges to address when establishing community gardens in low-income, minority communities. First, it is essential to understand residents’ preferences for community gardens in these neighborhoods. Some studies indicate that the culture surrounding local and healthy food from UA is often associated with communities that have higher education levels and incomes (Bellemare and Dusoruth, 2021), while others find no significant differences in preferences for community gardens across income and racial groups (Li & Long, 2024). This variability highlights the need for community-specific assessments to tailor UA initiatives. Engaging residents in planning ensures that the gardens align with the needs of the neighborhood, promoting greater utilization and sustainability. Second, the impact of community gardens on these communities requires further examination. While these gardens can improve access to fresh food and green space, they may also contribute to rising property values (Voicu and Been, 2008), attracting more affluent households and potentially leading to gentrification and displacement of existing residents. Therefore, it is important for city planners to balance the benefits of community gardens with proactive measures to mitigate the potential displacement risks.

Reference:

Bellemare, M. F., & Dusoruth, V. (2021). Who participates in urban agriculture? An empirical analysis. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 430-442.

Clark, J. K., Conley, B., & Raja, S. (2021). Essential, fragile, and invisible community food infrastructure: The role of urban governments in the United States. Food Policy, 103, 102014.

Feeding America. (2024.). Map the Meal Gap: Executive Summary. Feeding America. Retrieved October 25, 2024, from https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/map-the-meal-gap/overall-executive-summary

Guitart, D., Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2012). Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban forestry & urban greening, 11(4), 364-373.

Kirby, C. K., Specht, K., Fox-Kämper, R., Hawes, J. K., Cohen, N., Caputo, S., … & Blythe, C. (2021). Differences in motivations and social impacts across urban agriculture types: Case studies in Europe and the US. Landscape and Urban Planning, 212, 104110.

Li, L., & Long, D. (2024). Who values urban community gardens and how much?. Food Policy, 126, 102649.

Voicu, I., & Been, V. (2008). The effect of community gardens on neighboring property values. Real Estate Economics, 36(2), 241-283.

Li, Liqing. “Urban Agriculture in the South: Addressing Food Insecurity and Social Inequality through Community Gardens.” Southern Ag Today 4(46.5). November 15, 2024. Permalink