Eunchun Park, Christopher N. Boyer, and Clinton L. Neill[1]

The live-to-cutout beef price spread is the difference between the value of boxed beef and the price paid for live cattle and is a commonly used metric in the industry. This article summarizes a recent paper by Park et al. (2025) that used this metric to explore what happens to the differences in these prices when beef packers process capacity changes. Specifically, this paper explores what happens to the price spread when a processing plant goes offline temporarily or permanently.

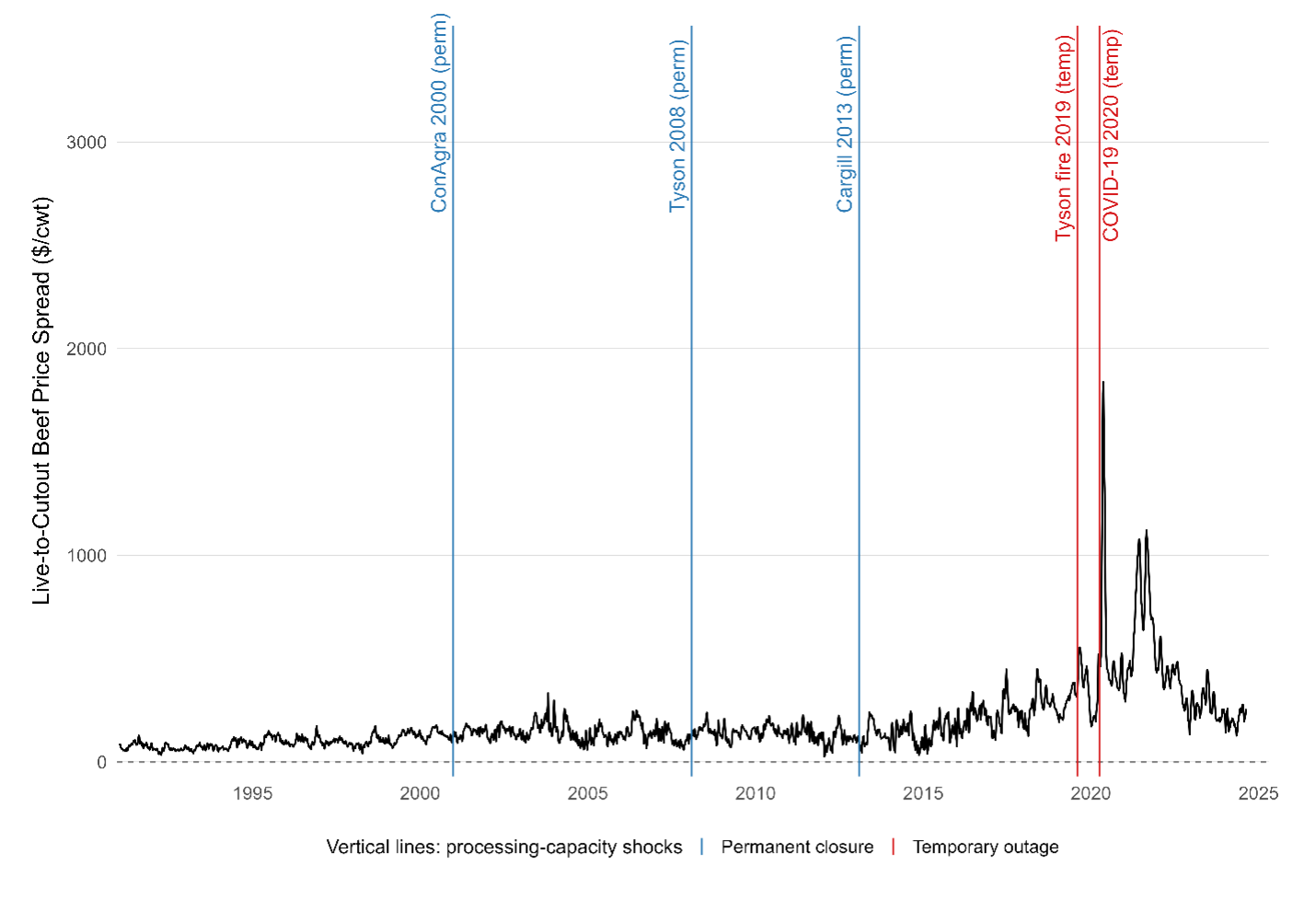

The key distinction between a temporary and or permanent closure is temporary closures are often unexpected, with short notice, while permanent closures might be more telegraphed or planned. Temporary outages—such as the Tyson Holcomb fire in August 2019 or the COVID-19 disruptions in spring 2020—remove effective capacity without warning. In those periods, the study found the price spread tends to move to a higher level with greater week-to-week volatility, and that wide-band behavior often persists for several weeks before normalizing. By contrast, permanent closures are generally announced in advance, allowing time to adjust cattle flows, freight, and line schedules. Because the industry can prepare, the spread before and after a permanent closure typically resembles normal trading conditions.

Figure 1 illustrates these patterns. The black line shows the weekly live-to-cutout spread. Blue vertical lines denote permanent closures (ConAgra 2000; Tyson 2008; Cargill 2013), while red lines denote temporary outages (Tyson fire 2019; COVID-19 2020). Around permanent closures, the spread looks normal. Around temporary outages, it jumps and stays jumpy for several weeks. The temporary events align with sharp run-ups and a bumpier path in the weeks that follow.

The implications of this study differ by audience. For producers and feedyards, treat the first two to four weeks after an unexpected outage as a high-variance window. Expect a higher average spread and larger week-to-week swings at the same time. Maintain an additional working-capital cushion, widen basis and grid bands in cash-flow plans, and be conservative on marginal pens. If marketing on the grid, expect greater dispersion and review terms that are usually taken for granted when capacity is tight. For lenders and risk managers, stress tests should raise both the level and the variance of the spread, with horizons long enough to cover the typical persistence of the high-regime window.

Permanent closures call for a different approach. When changes are announced and phased in, the market usually adapts without dramatic swings in the spread. The task is primarily logistical—update cattle routing, confirm shackle space, and revise freight and plant schedules—while keeping standard cash-flow settings.

Why rely on the spread? It is public, timely, and can reflect packer margins and producer net prices. When capacity tightens, harvest slows, boxed beef firms, and the spread widens—often before other indicators move. No complex model is required; it is enough to know the usual range for your region and when to widen operating bands.

In short, temporary, unexpected outages create brief intervals when the spread runs higher and volatility increases; plan the first month around that reality. Permanent, telegraphed closures generally allow the industry to adjust with less disruption. Match the playbook to the shock type to reduce hurried decisions when plants stop.

Figure 1. Weekly live-to-cutout beef price spread ($/cwt), 1992–2024. Vertical lines mark processing-capacity shocks: blue = permanent closures (ConAgra 2000; Tyson 2008; Cargill 2013) and red = temporary outages (Tyson Holcomb fire 2019; COVID-19 2020). Temporary shocks coincide with short-lived regime shifts—higher levels and choppier volatility—while permanent closures show little persistent change in the spread.

References

Park, E., Boyer, C. N., and Neill, C. L. (2025). A Markov regime-switching event response model: beef price spread response to processing capacity shocks. Empirical Economics, 68:1039–107.

[1] Eunchun Park is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness / Fryar Price Risk Management Center of Excellence at the University of Arkansas, Christopher N. Boyer is a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of Tennessee, and Clinton L. Neill is an adjunct assistant professor Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences at Cornell University.